The Myth of Equal Outcomes

Nature, culture and the case for equality of opportunity and the necessity for the inequality of outcome

“Equity should mean removing obstacles, not falsifying results.”

I. A Shared Species, Divergent Stories

All humans today belong to Homo sapiens sapiens. Yet within that shared frame, nature has painted with a nuanced palette. Different populations adapted to their environments over tens of thousands of years. These adaptations—biological, cultural, and cognitive—produced distinct characteristics that continue to shape outcomes today.

Modern discourse often recoils from acknowledging such differences, fearing that any admission of disparity becomes a justification for discrimination. But truth, carefully and respectfully held, is the foundation of a functional society. And the truth is this: we are not all identical. And that’s not a problem.

II. Genetic Admixture and the Legacy of Deep Time

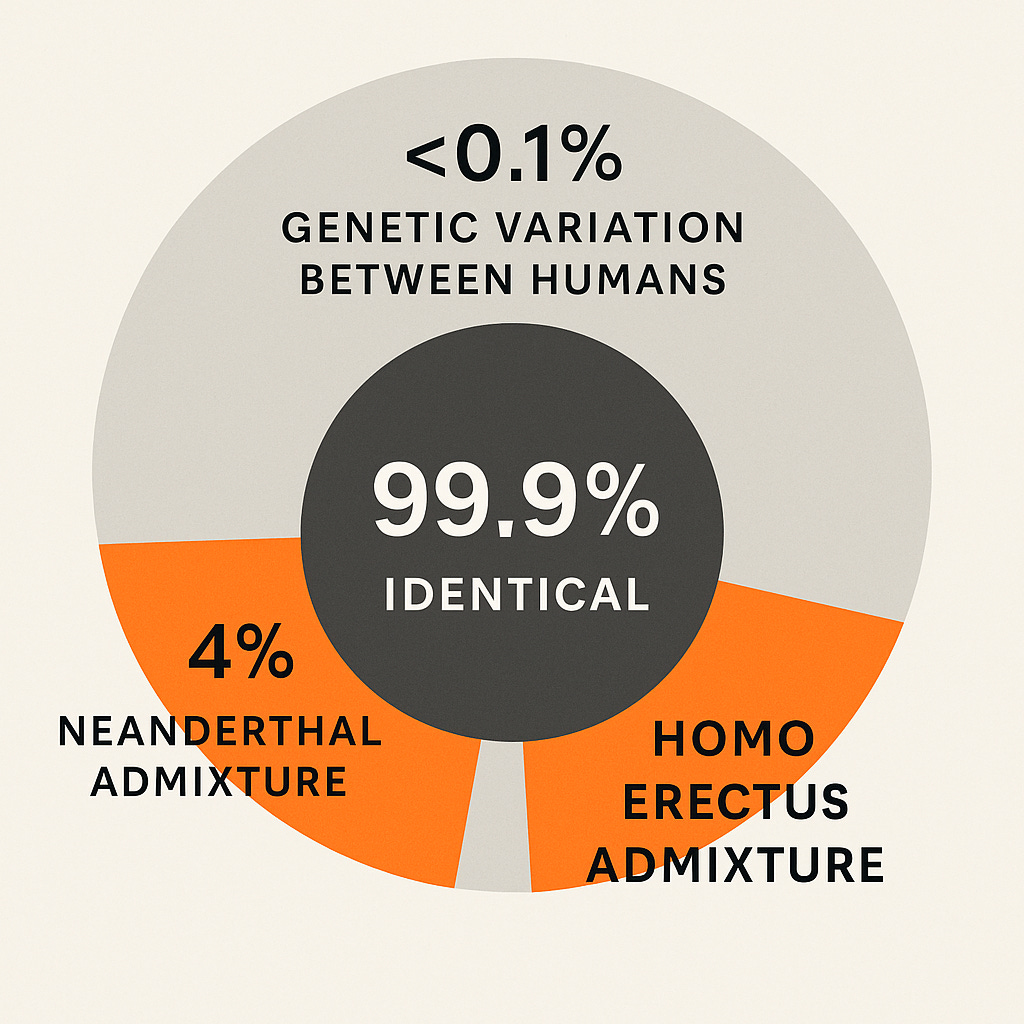

DNA tells a subtle story. While the genetic variation between human populations is very small—less than 0.1%—there are meaningful differences.

Europeans carry around 2–4% Neanderthal DNA.

East Asians and Melanesians carry a smaller admixture of Denisovan DNA.

Sub-Saharan Africans, closest to the human origin point, exhibit the highest overall genetic diversity, but less Neanderthal admixture.

These ancestral traces do not necessarily imply superiority or inferiority—only different paths through evolutionary history.

(This DNA admixture is a bit confusing and I’ve tried to make it more clear in the Appendix for those interested in a deeper dive.)

III. Physical and Developmental Realities

Differences are observable, especially in:

Maturation: Black children, on average, enter puberty earlier.

Hormonal profiles: Some studies show higher testosterone levels in African-American men compared to whites or Asians.

Athletic performance: Variability in muscle fiber type, lung capacity, and limb proportions explain population-level trends in elite sports.

These traits are evolutionary responses to climate, geography, and lifestyle. They are not destiny—but they do affect outcomes.

IV. Cognitive Distribution and IQ

IQ is not a perfect metric, but it does correlate with academic and professional success. Global studies reveal average scores:

East Asian populations: ~105

European populations: ~100

African-American populations: ~85

Sub-Saharan Africa: ~70–80

It should be noted that the US Army generally mandates IQs of around 83 and above and has found that recruits below 80 could not master modern soldier skillsets.

These figures reflect both genetics and environment. Factors like malnutrition, stress, trauma, educational quality, and lead exposure all suppress cognitive performance. The lower scores observed in some regions are not necessarily indictments of potential—they are snapshots in time.

Importantly: distributions overlap significantly. Individuals of high ability exist in every group, and societal contributions are never reducible to IQ alone.

V. The Geography of Civilisation

It is sometimes claimed that sub-Saharan Africa “never developed” the wheel, written language, or monumental architecture. That is somewhat misleading.

The Bantu expansion spread agriculture and metallurgy across the continent.

Timbuktu was a centre of Islamic scholarship in the 14th century.

The Ethiopian empire had Christianity and literature centuries before northern Europe.

However it is certainly true to say that sub Saharan Africa has very few great achievements to claim of its own and recent advances such as they have been are largely due to European, Arab and Chinese influences.

Civilisational development to some extent correlates more with geography and environment than race:

Eurasia’s east-west axis allowed the spread of crops and ideas.

Africa’s north-south axis traversed radically different climates, making diffusion difficult.

Domesticable animals and high-calorie crops were fewer in Africa and the Americas.

Of course this is simply another way of saying that differences between the races were cemented over long periods of time and are a real observable characteristic in the here and now.

VI. The Problem With Equity of Outcomes

There is an important distinction:

Equality of opportunity ensures that all are free to try.

Equity of outcome assumes that unequal results are unjust by default.

The latter view ignores the complex interplay of culture, values, biology, and choice. Not every group will excel at the same things. Expecting parity in every field leads to:

Quotas over merit

Resentment over fairness

The silencing of inconvenient truths

This does not mean we abandon fairness—it means we stop demanding sameness.

VII. What Should a Fair Society Do?

Remove artificial barriers—racism, poverty, broken schools, inherited trauma.

Recognise excellence wherever it arises—regardless of race or background.

Accept variance—not as injustice, but as the natural outcome of freedom.

Preserve dignity—remembering that worth is not defined by output.

We can and must continue to care for all citizens. But we must stop confusing care with coercion. To force parity in every field is not just unrealistic—it is profoundly anti-human.

VIII. A Closing Thought

Human difference is not a flaw in the design—it is the design. To deny those differences is to deny nature, history, and agency. Let us seek just systems, not rigged outcomes. Let us celebrate the lily for blooming in its own time—not for matching the rose.

Appendix 🔍 How is it possible to be 99.9% identical if some of us have Neanderthal or Erectus DNA? What “99.9% Identical” Really Means?

This number refers to variation within modern Homo sapiens. That is:

You take any two modern humans, compare their ~3 billion DNA base pairs.

About 99.9% of those base pairs will be identical.

The remaining ~0.1% accounts for all the observable diversity in traits.

Importantly, this includes Neanderthal or Denisovan DNA, because:

Those sequences have been introgressed (integrated) into the modern human genome for over 40,000 years and are now considered part of the variation within Homo sapiens.

🧬 Admixture: Foreign Code Now Fully Human

When you hear “4% Neanderthal DNA” in a European genome:

That doesn’t mean you have an extra 4% of genome beyond what a human has.

Rather, it means that in 4% of your genome, the variant version of a gene (or sequence) matches what was found in Neanderthals, not the African ancestral type.

These segments are part of your 3-billion-base-pair genome, so the total size is still the same—it’s the origin of the sequence that differs.

Similarly:

Claims of "10% Homo erectus" DNA in some African populations are speculative and controversial—but even if true, the same logic applies: those ancient genes are now part of the variation within the modern Homo sapiens genome.

🧠 A Useful Analogy

Imagine the human genome as a vast library with 3 billion books (base pairs).

99.9% of the books in your library are identical to the books in your neighbour’s.

But in 0.1% of books, you might have the “Neanderthal edition,” and your neighbour might have a different variation—some of which may come from a Homo erectus source.

The book count doesn’t change—just which edition is on the shelf.